NOTE: Yankee Go Home is a bilingual newsletter. You can read the German-language version of this article here.

Dear friends in Germany,

When I was seven, and my sister was four, I taught her to read and write in English.

We set about the task with all the confidence of youth, never imagining that our project had the slightest chance of failure. In fact, I took it seriously enough that my sister would sometimes run sobbing to Mom or Dad: “John gave me homework!”

While I was tutoring her, our parents were deep in their own language studies. They would rise every morning to drive the steep serpentine roads to the Goethe Institut in the Rhein Valley below. For two years, they diligently trained their adult monolingual brains to pray, preach, and klatsch in the German language.

“Military brat?”

That’s the usual response when I mention that I grew up in West Germany.

No, Dad wasn’t in the service. Not that service, anyway. It would be years before we even had G.I. friends to take us on-base at Rhein-Main or Heidelberg to hit a Stars & Stripes bookstore. There was no Reddit, no Sky Channel, no cultural bubble for Americans to retreat into. In a connected world, expats can selectively opt out of assimilation. In Cold War Germany, we didn’t have that choice.

But that didn’t matter. We hadn’t moved to Germany to be conspicuously American. We had moved to be conspicuously Christian. Assimilation was a given. My sister and I picked up the language effortlessly: from playgrounds, Lustige Taschenbücher, and anime dubs of Heidi and Captain Future on ZDF. On my first day of first grade, I carried a traditional Schultüte. I wore Lederhosen and called myself Johann. (Over the years, that softened to Hans before finally reverting to John. The Lederhosen disappeared on day 2.)

Our language problem was the opposite of our parents'. Expat families can start losing their mother tongue without even realizing it. Years of linguistic drift can even lead to a hyperlocal patois that is unique to just one nuclear family or household. I’ve seen it happen.

I didn’t understand those dynamics at age seven, but I still set about my sister’s instruction with some urgency and clarity of purpose.

You see, there was one unique lifeline to my passport country: the occasional box full of English-language books that would appear on our doorstep. These arrived sporadically, covered in sheets of stamps and filled with haphazard donations from the American churches that supported my parents’ missionary work. Those books became personal totems to me. They were magical portals to a birth culture that I missed with a special homesickness, and that felt galaxies away from Boppard am Rhein.

I sensed that my little sister would lose something invaluable should these portals remain closed to her. So I sat her down. And I gave her the homework. She was reading English fluently long before she entered German Kindergarten.

There's a reason I’m telling you this story. I taught my sister to read using educational materials from a company called Abeka. These “Beka Books” taught us phonics, but the curriculum held other lessons, too.

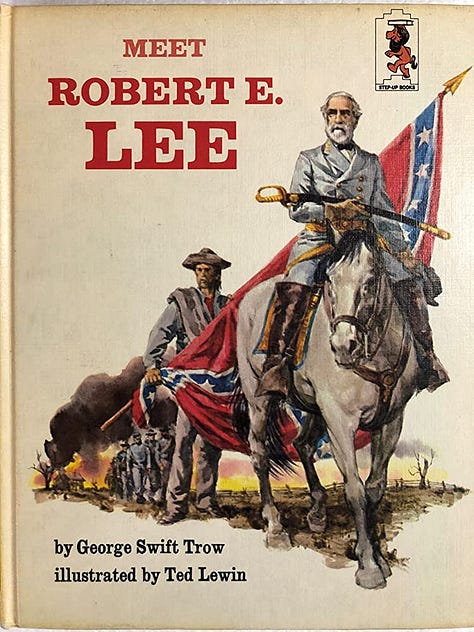

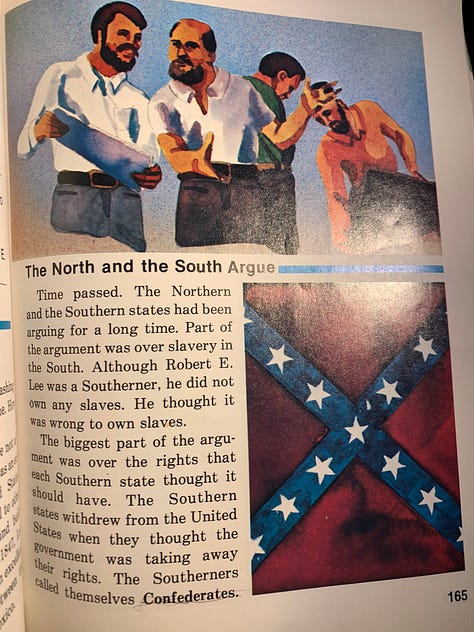

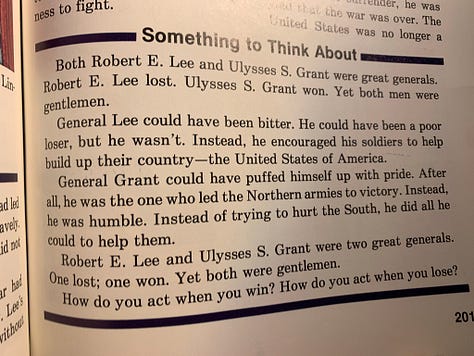

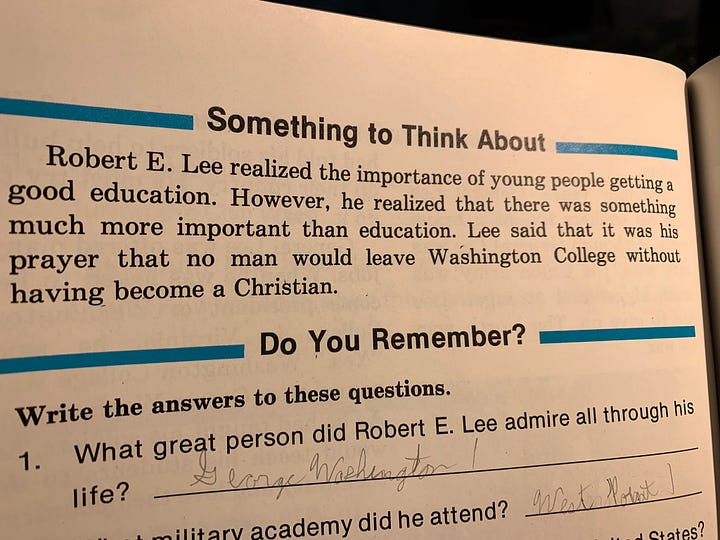

For example, they taught that Robert E. Lee (the commander of all Confederate forces during the American civil war) was a great patriot, a great Christian, and a great American. They taught that American chattel slavery was mild. They portrayed a system that had been mostly kind, and ultimately of great benefit to the kidnapped and enslaved people. Above all, Abeka's books described my far-off home as founded to be an explicitly Christian nation whose actions throughout history were uniquely blessed by God.

The head of our missionary organization had strongly recommended these books before we emigrated. As far as I know, he had no strong personal loyalties to the Southern “Lost Cause”. Nor did my parents—we considered ourselves Northerners. We were Yankees. My evangelist grandfather raised his five children to reject the racist theological doctrine known as “the curse of Ham". And when Nord Und Süden played on TV, we knew that the soldiers in blue were the good guys.

Still, the Confederate apologia wasn’t just sprinkled into elementary reading primers. It was also in the occasional book that fell from those magical boxes. This wasn’t controversial in my world. It wasn’t mentioned at all.

I’ve included a few images here by way of illustration.

In those first German years, before we moved to a small suburb in Hessen, I would spend many days playing alone in the hills. I'd build forts and fashion crude bows and arrows. I plucked wild black raspberries. I'd peer across the valley to the Feindlichen Brüder on the opposite hill, two tiny castles barely worthy of the name. I tried to imagine the many heroic battles that must have been fought there.

I still think about that kid on the hill sometimes. And I think about how even then—in 1981, perched high above Kilometer 566 on the Rhein—there were already propaganda networks that could reach across the Atlantic Ocean and plant white supremacist ideas in my young mind.

These days my thoughts turn to Germany more and more. My European networks have been buzzing since 2016 as I’ve spoken with former church elders, teachers, and boarding school comrades.

We have questions for each other.

Mine boil down to: How bad does America’s situation look from over there?

They simply want to know: "How the hell did Donald Trump happen?" And why are all my American Christian friends so indignantly truculent when I ask the question?

I've been working on these questions for a while now. I’m not finished with that work, but it’s time for me to start connecting a few dots for you.

I started writing this epistle to offer a somewhat rare perspective: that of an evangelical Missionary Kid who grew up German. There’s a line in Craig Mazin’s Chernobyl series: “They’re not letting children play outdoors… in Frankfurt.” That kid in Frankfurt? That was me.

So I feel a responsibility to you, dear Dani, Hartmut, and Jörg; dear Ulli and Erik; dear Felix and Corinna and Larissa; and dear Alexandra and Tomas and Millay; as well as to the church in Rödermark that my father planted 37 years ago.

But I’m also writing this to all of Germany: if you’re concerned or curious about what’s happening in my homeland, please eavesdrop. This concerns you, too.

I recently rewatched the German film Das Weisse Band. These words from Michael Hanneke simply will not stop rattling around my head:

I don't know if the story that I want to tell you reflects the truth in every detail. But I believe I must tell of the strange events that occurred in our village, because they may cast a new light on some of the goings-on in this country.

I’m not offering you a manifesto or a comprehensive intellectual history. I’m neither scholar nor guru. But I am still that German kid who stood in the pews singing Bonhoeffer’s Von Guten Mächten, and cried his eyes out at the end of Winnetou III.

If that lends us any affinity whatsoever, I’d like to offer you something simpler. This is my testimony to you.

As the Apostle Paul said: I would not have you be ignorant on these matters.

John Eremic

September 2024